[ad_1]

In Might 1923 the German curator Gustav Friedrich Hartlaub wrote to a coterie of artwork sellers, collectors, and fellow curators with an idea for an exhibition to which, he hoped, they may lend some footage. He needed latest works that had been “neither impressionistically relaxed nor expressionistically summary” however “trustworthy to constructive palpable actuality.” A liberal with broad art-historical pursuits, Hartlaub had appreciated expressionism, Germany’s main avant-garde tendency earlier than World Struggle I. However expressionism appeared insufficient to the developments that adopted. Germans who had been invested within the restoration of their social and creative lives after 1919 felt that the motion celebrated, even exacerbated, the continued nationwide chaos; these eyeing revolution typically considered the artists’ emphasis on subjective expression as an indication of social and political withdrawal. Already throughout the conflict, and much more thereafter, artists affiliated with political and aesthetic avant-gardes (Hartlaub cites the erstwhile Dadaists George Grosz and Georg Scholz) had been buying and selling “deskilled” or modernist types like abstraction and collage for figurative portray and drawing. Various in type and substance, the brand new work nonetheless cohered sufficient for Hartlaub to present it a reputation: “die neue Sachlichkeit.”

Typically translated as “objectivity,” Sachlichkeit connoted much less a technique than an epochal sensibility—a deal with “palpable actuality,” on “issues” and “details” (two phrases with etymological hyperlinks in German to Sachlichkeit). After the exhibition opened in June 1925 on the Kunsthalle Mannheim, Hartlaub’s time period expanded past a broad corpus of portray to explain a bunch of different types: documentary images, functionalist structure, journalistic fiction, epic theater. “There’s an objectivity [Sachlichkeit] floating within the air,” went the refrain of a preferred 1928 tune. It was an apt metaphor: the idea was rising vaporous.

Hartlaub admitted as a lot the next 12 months in a letter to Alfred H. Barr Jr., director of the soon-to-open Museum of Trendy Artwork. At its outset, wrote Hartlaub, Neue Sachlichkeit referred to an “total temper at the moment”—the years riven by the aftermath of mechanized warfare, thwarted revolution, and hyperinflation. But by the summer season of 1929, close to the shut of Germany’s interval of relative financial stability, the time period had misplaced not solely its precision but in addition its historic necessity. “The buzzword is usually misused at the moment,” Hartlaub concluded, “and it’s time to abolish it.”

Reasonably than rejecting it (or pinning it down), an exhibition on the Centre Pompidou reproduces New Objectivity’s authentic diffusion. The curators, Angela Lampe and Florian Ebner, show dozens of work alongside different emblems of 1920s German tradition—pictures, movies, furnishings, house items, books, archival supplies—a few of them assimilable to New Objectivity and others not. Visible and tonal echoes abound: a Marcel Breuer chair reappears in two dimensions on a close-by canvas by Karl Hubbuch; Grosz and Anton Räderscheidt paint the boxy, modernist buildings seen elsewhere in pictures by Werner Mantz. When the anticipated icons of Weimar-era Berlin seem, like Otto Dix’s portrait of the dancer Anita Berber, they accomplish that as pendants of a variegated cultural profusion borne of a society much less “secure” than its reformist politicians claimed it was and fewer amenable to “objectivity” than its cultural officers may need hoped.

Lampe and Ebner use two framing units to convey these disparate objects collectively. The primary is to divide them throughout eleven themed galleries devoted to financial and social phenomena, like “Standardization” and “Transgressions,” or to strategies, like “Montage.” The second is to set the works in dialog with a single challenge by the photographer August Sander (1876–1964)—his sequence Folks of the Twentieth Century, which fills a big, V-shaped space that cuts via the exhibition.

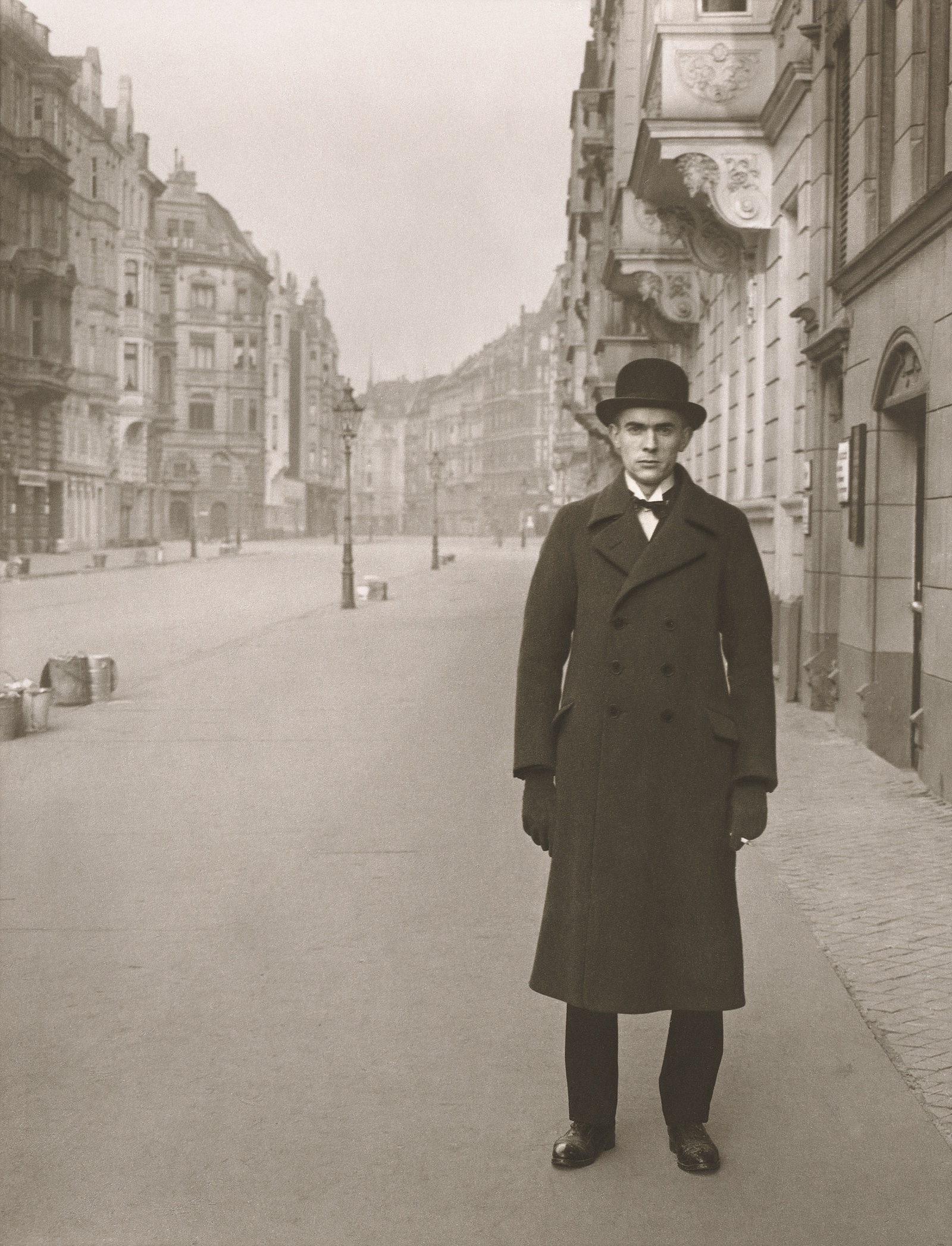

A decades-long, unfinished challenge, Folks has lengthy been thought to be exemplary of the New Objectivity, which, coined to explain portray, little question lent itself to images, a medium unequalled in its readability or, in Sander’s phrases, its “terrifying truthfulness.” “Nothing appears higher suited than images to present a completely trustworthy historic image of our time,” he wrote in 1927. For Lampe and Ebner, Folks stays productive alongside these strains: it “runs via the exhibition,” the opening wall textual content tells us, “in the identical approach because it ran via its interval.” The challenge was not solely historic but in addition scientific; with it, Sander proposed to doc a cross-section of German society. He photographed representatives of assorted lessons and identification teams, fixing them into seven classes with a developmental schema that moved from the pre-industrial “Farmer” to professions fashioned by industrialization to the “Final Folks,” particularly these with disabilities.

For all of the social stratification they show, the pictures have related compositional codecs. Spurning the ornate predilections of earlier studio images, Sander snaps his topics in entrance of clean partitions or on the road; centered, they strike demure however evocative poses, rendered in what Dix praised, in a letter to Sander, as “an nearly abstractly unreal sharpness.” In a typical scene, an “itinerant actor” (1928–1930) gestures as if mid-monologue. The pose communicates his line of labor; the heavy luggage below his eyes recommend his career’s bodily toll.

Some later critics have seemed askance at Folks. In 1981 the author and photographer Allan Sekula chided the “universalism of Sander’s argument for photographic and physiognomic reality,” situating the challenge inside the interlocked histories of bourgeois portraiture, positivist science, and one among images’s, if not Sander’s, pivotal early capabilities: the formation of carceral archives. The sharp objectivity of every {photograph}—its obvious immediacy, even realism—conceals, to Sekula, the technical and historic processes that enabled its manufacturing. However whereas Sekula thought that Sander naturalized capitalism’s social order, a few of Sander’s Marxist contemporaries noticed a vital impulse in his work.

The Cologne artist, author, and Sander affiliate Franz Wilhelm Seiwert thought that Folks confirmed nice promise. Reviewing Face of Our Time, a 1929 assortment of Sander’s photographs, Seiwert quotes the preface to Capital to recommend that Sander’s challenge, if it solely had “a sharper and clearer” classification system, would strategy Marx’s personal “sociological” one. (“People are handled right here,” goes the quotation, “solely in as far as they’re the personifications of financial classes, the bearers of explicit class-relations and pursuits.”) For Walter Benjamin, too, Sander’s archive was not insidious however instructive. If, as Sekula notes, an emphasis on the legibility of physiognomy and the definition of a topic by their capability to work would quickly serve authoritarian functions, in 1931 Benjamin may nonetheless argue that such recognition fostered class consciousness and solidarity. Ongoing “shifts of energy,” he thought, “make the flexibility to learn facial sorts a matter of significant significance.” Sander’s footage, in different phrases, appeared to vow that an individual’s face may inform you in the event that they had been, or weren’t, in your aspect.

Sander apart, Benjamin and his friends dismissed New Objectivity, particularly within the mediums to which they had been most critically attuned: specifically literature, the place practitioners prioritized reportage and floor description, and images, particularly its landscapes and interiors. Purporting to matter-of-factness, such paperwork supplied, to the thinker Ernst Bloch, “nothing however sheer façade.” Their consideration to what was “palpable” hid no matter contradictions lay beneath. The type’s “deception,” Bloch added, “largely prevents it from being disruptive within the capitalist financial system.” On this, the work mirrored the contradictions of one among its predominant audiences, the emergent white-collar “salaried lots” who Bloch and his fellow critic Siegfried Kracauer thought suffered from false consciousness: they aligned with the bourgeoisie of their habits of consumption regardless of being nearer to the blue-collar employees’ relationship to manufacturing.

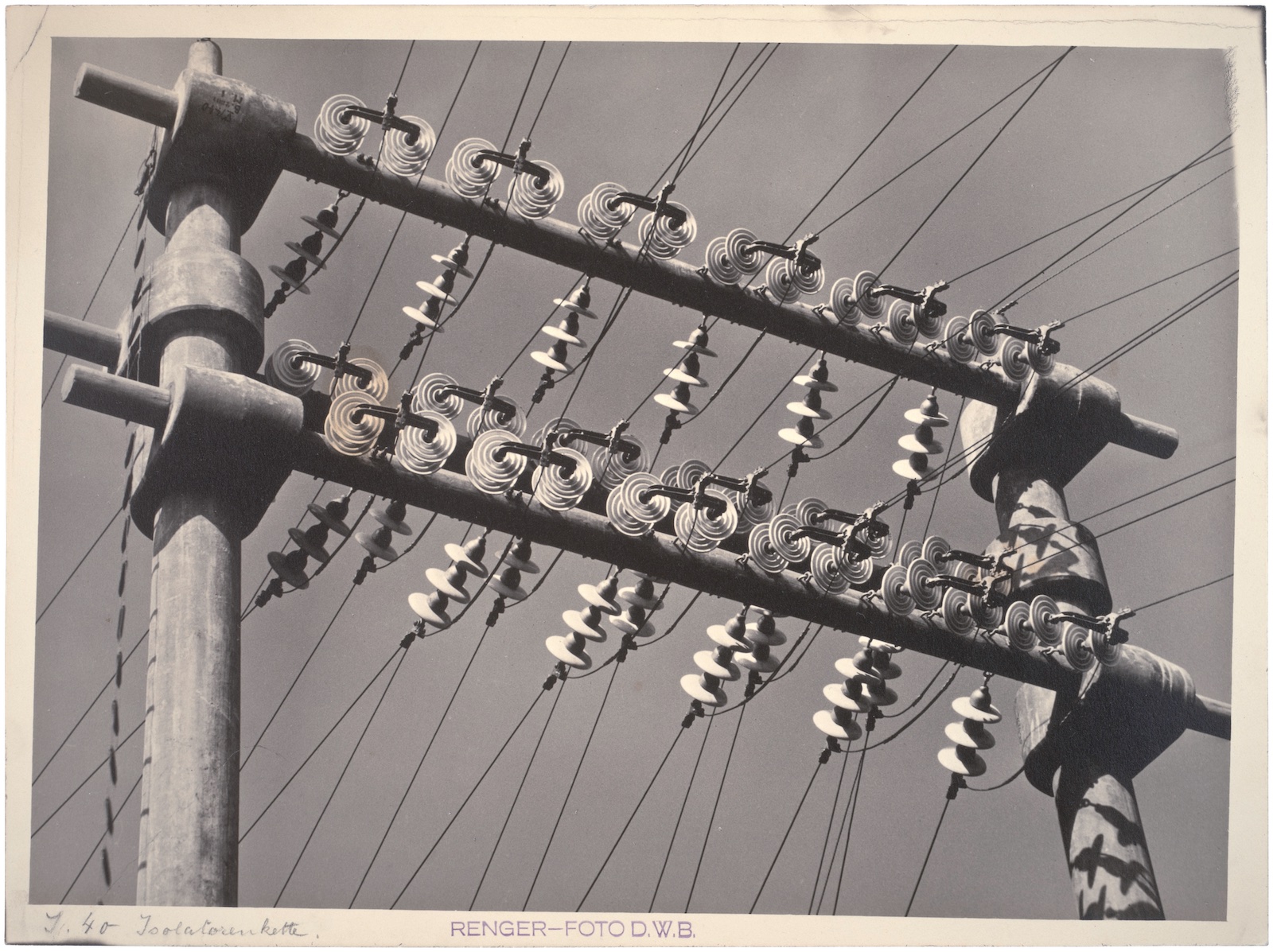

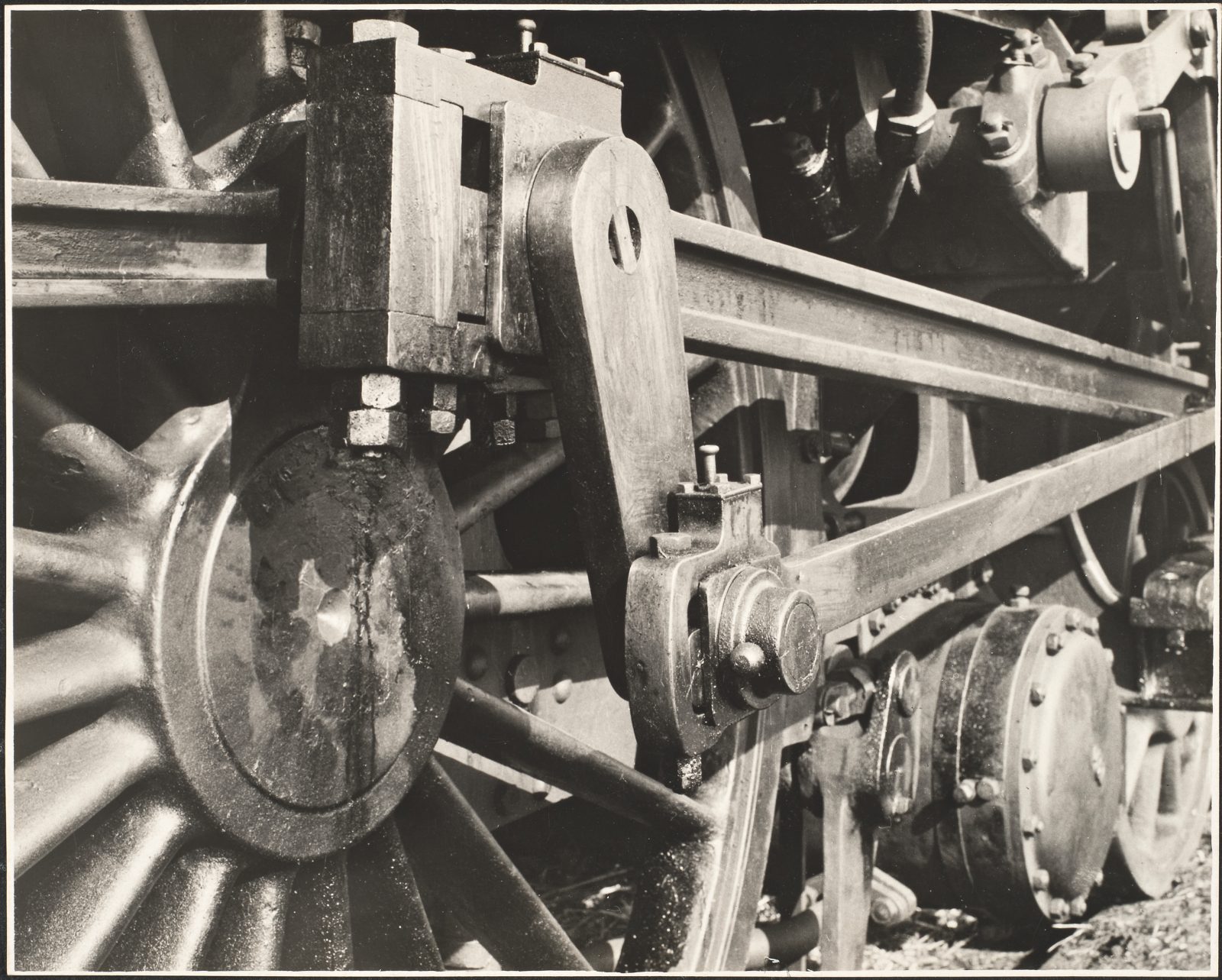

To the critics, falsity outlined writers like Erich Kästner (whom Benjamin charged with “left-wing melancholy” and whose fashionable, descriptive poetry is excerpted on partitions on the Pompidou) and photographers like Albert Renger-Patzsch. The latter’s sharp industrial scenes, some on show within the exhibition, mystified manufacturing unit circumstances quite than clarifying them. With out human topics, these footage of the websites and merchandise of the Fordist manufacturing that, an increasing number of, drove Weimar Germany’s financial development made viewers really feel that they, too, had been exchangeable, thing-like. If {a photograph} by Renger-Patzsch “can endow any soup can with cosmic significance,” Benjamin supplied, it “can’t grasp a single one of many human connections through which it exists.” It’s simple to see his level within the lurching, nearly motile stacks of aluminum pots in Aluminiumtöpfe (1925). What was at stake in widespread devotion to objectivity was, in impact, a denial of subjectivity, of human company.

The issue was not images itself. To interval critics of New Objectivity, images and particularly movie had been extra suitable than portray with the expertise of an electrified world, extra legible and accessible to the lots whose spirits they may energize—so long as the work was produced with the requisite formal and political vanguardism. Portray, in distinction, was a bourgeois relic. On the identical time, the medium clarified New Objectivity’s inside tensions: How, in spite of everything, may a picture as mediated as a portray be “goal”? How may such an index of sluggish human productiveness affirm the imperatives of a bourgeoisie now managing, and benefiting from, industrial manufacturing? Many work related to New Objectivity broach the urgent issues that, to the motion’s critics, its images and literature obscured.

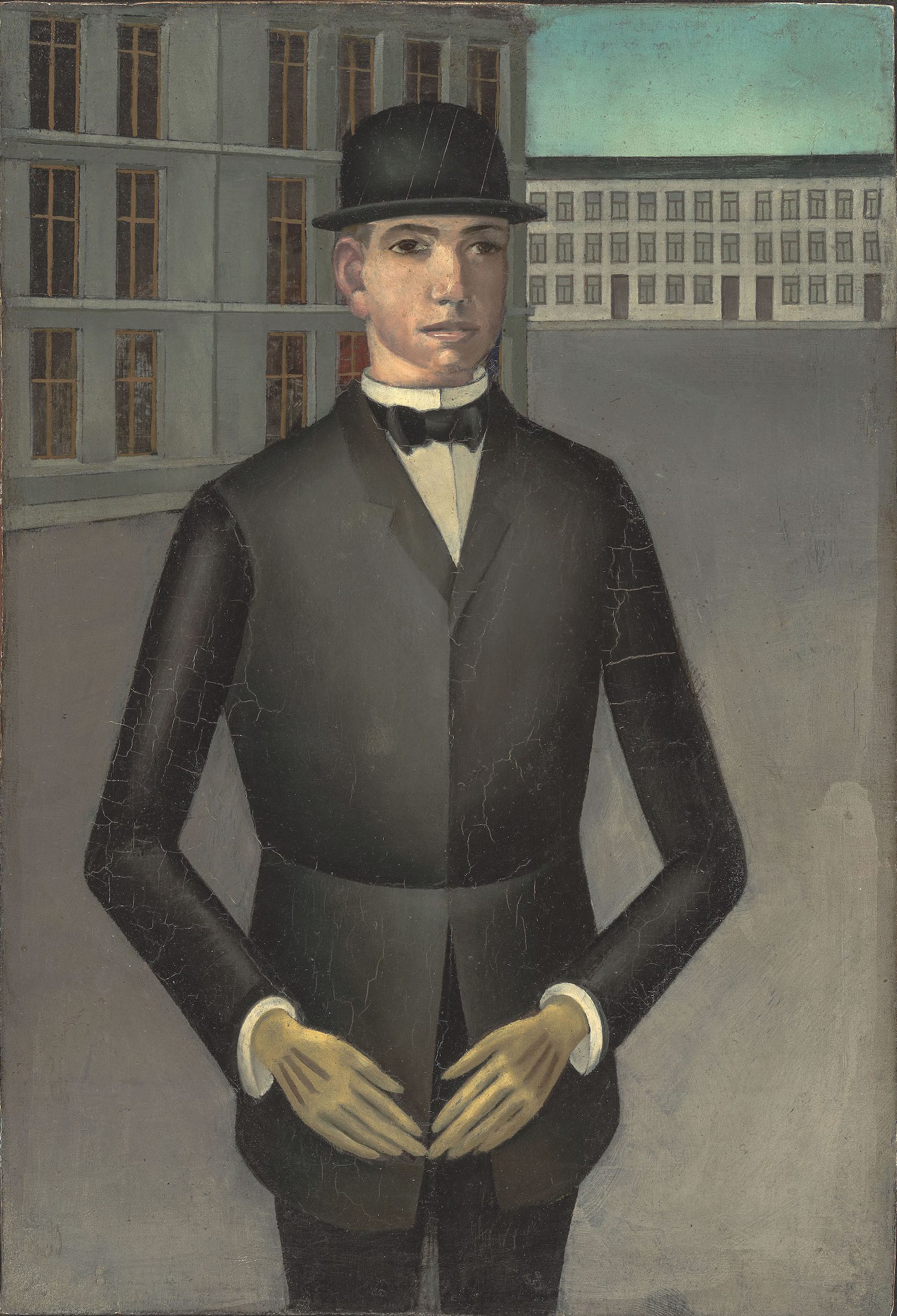

Taking their cue, immediately and not directly, from the elder Sander, a lot of the painters featured right here made portraits of consultant interval topics. As in Sander’s work, the sitters typically have an effect on what the curators, following the scholar Helmut Lethen, name a “chilly persona.” These work current stone-faced members of the brand new center lessons (medical doctors, artwork sellers, white-collar employees) whose “emotions,” Lethen has written, seem like “mere motor reflexes, and character is a matter of what masks is placed on.” Along with the anticipated city topics, the Pompidou present consists of footage of menial or artisanal vocations both enabled by the commercial revolution (like Scholz’s rural railway attendant) or reworked by it (Grethe Jürgens’s cagey retailers, wrapped in textiles that cloak the trendy enterprise apparel they put on beneath). Clear however not chilly, Scholz’s image, Bahnwärterhäuschen (1925), levels an unresolved battle between new (the streetlights and billboard at left) and outdated (the small oil lamp and darkened timber at proper). His anxious railway attendant opens the gate, ready for one aspect to overhaul the opposite. However which?

The truth that Scholz’s canvas is painted with technical precision raises a query central each to New Objectivity’s authentic formulation and to its postwar reception. Why use outdated strategies—like figurative portray—in a brand new world? Hartlaub closes his introduction to the 1925 Neue Sachlichkeit catalog with one reply. Towards ongoing threats to artwork and humanity, artists “have begun to ponder what’s most instant, sure, and sturdy,” he writes: “reality and craft.”

Compounding the threats of images and movie, Expressionism and Dada principally rejected conventional painterly craft, which their practitioners linked to bourgeois coaching and patronage, in favor of spontaneous or in any other case “deskilled” manufacturing. Many critics, each then and later, have subsequently understood New Objectivity’s reclamation of craft as an endorsement of the outdated order—the humanist, patriarchal system of Western portray that the avant-garde sought to overthrow. For the critic Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, the artists who referred to as for a return of illustration within the 1920s “den[ied] the dynamic flux of social life and historical past” in favor of an idealized “previous tradition.” Scholz appears a living proof: a participant within the First Worldwide Dada Honest in Berlin in 1920, he spent the second half of the last decade in southwest Germany honing his tutorial approach. Whereas his early work had lambasted the ruling class in simple phrases, with grotesque caricatures of landowners and politicians, his plaintive nation railway scene on the Pompidou affords, on its floor, a form of romantic anticapitalism.

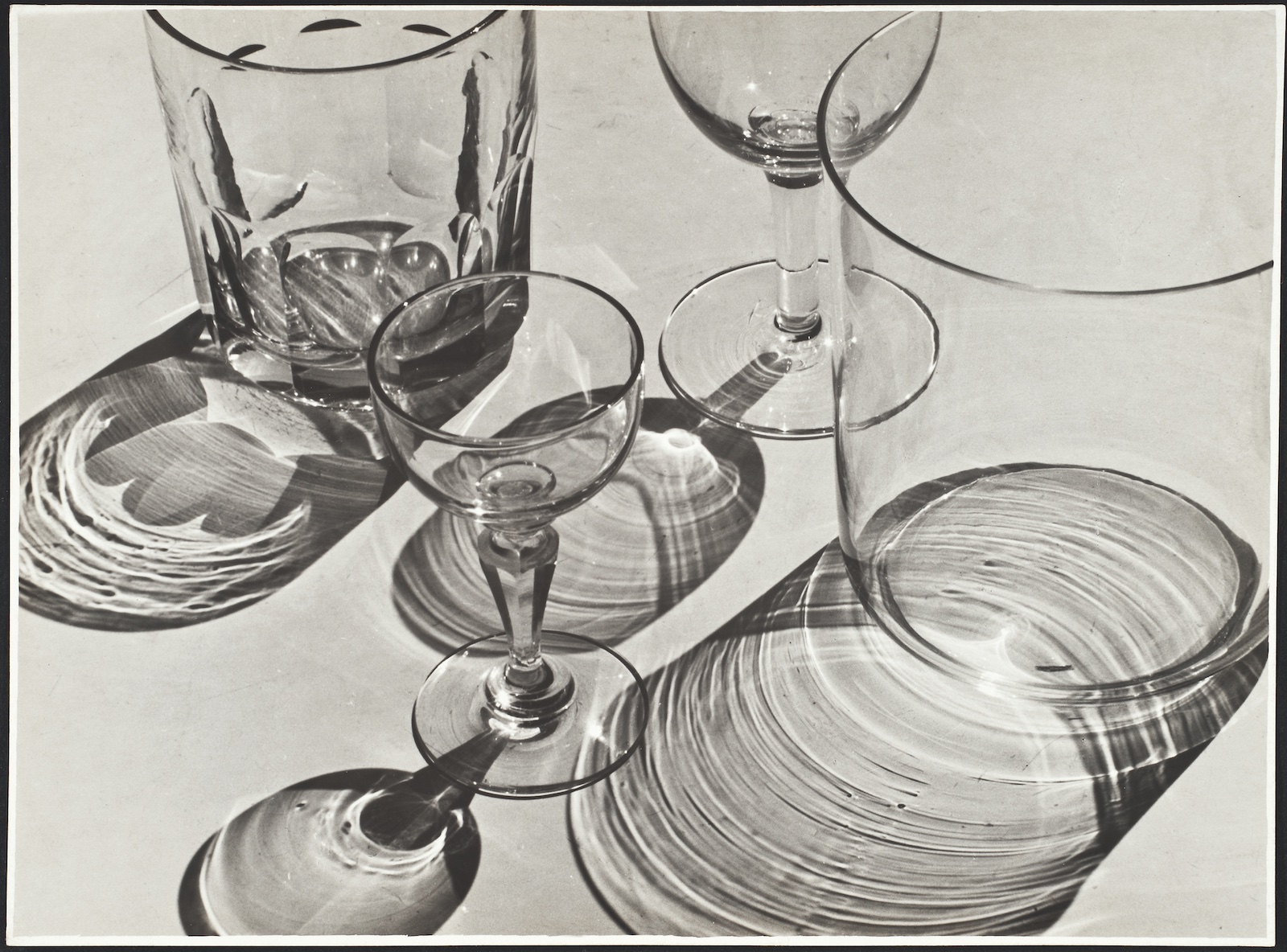

However the exhibition extra typically goals to rebut critiques like Buchloh’s, both by displaying that some painters related to New Objectivity actually depicted dynamic social flux (like Jeanne Mammen did in her scenes of queer nightlife) or by arguing for structural affinities between portray and vanguard artwork (Hubbuch’s montage-like compositions). A number of the picks—like Christian Schad’s earthy portrait of a girl in Italy (1927), the place Schad lived and studied the Outdated Masters—do repeat pictorial conventions of the Renaissance. Others, nevertheless, prod at Western portray’s very conventionality. In Weiblicher Akt auf dem Couch (1928), Scholz illustrates a recumbent nude, a traditional train. However he pulls again the curtain, portray the period-specific particulars that tutorial artists may crop out: trinkets in the appropriate foreground and a gramophone at left. Hannah Höch, higher identified for her photomontages, affords a covert self-portrait in Gläser (1927), a blurred picture of the artist mirrored in a still-life’s glass bottle. A close-by wall textual content notes that tumbler was an indication for transparency, a assure of objectivity. However for Höch, the fabric implicates the painter’s subjective selections as a substitute—what to color, the place to sit down.

A number of canvases present their creators with brush in hand and inquire into the painter’s social function at a time of intensive financial and technological change. In Selbstbildnis (1928), Anton Räderscheidt paints himself in a sterile room, standing in entrance of a canvas that incorporates a portrait of his spouse, the artist Marta Hegemann. The 2 look uncannily alike, as if to establish portray with self-fashioning and gender presentation—or, on the identical time, to handle the persistent dynamic of man as artist and girl as mannequin. Wearing enterprise apparel and affecting that chilly countenance of the center class, Räderscheidt additionally indicators that, amid modern corporatization and the professionalization of creative labor (typically in Germany’s burgeoning promoting and design industries), portray could finest be approached as workplace work. Rendering himself in a swimsuit and tie, the Bauhaus-trained artist Carl Grossberg casts himself as an engineer; having overseen the development of the machine to his left, one imagines, he’ll now start sketches for no matter will grow to be of the clean, boxy buildings to his proper. In a previous gallery, a close-cropped image of Franz Lenk’s humble workstation hangs subsequent to a picture of cleansing provides by Hans Mertens. Comparable each of their tone and of their small format, the works establish portray not as workplace however home labor.

Some artists engaged, pictorially and politically, with the proletariat—normally with empathy, if not fairly identification. Karl Völker reveals employees as a collective on their commutes or breaks, in austere settings, with standardized faces that broadcast shared alienation. Hans Baluschek’s Sommerabend (1928) reveals a extra differentiated group of {couples} and kids, resting exterior within the night in entrance of a tenement constructing. Seiwert’s employees in Die Arbeitsmänner (1925) lack the realist look of Baluschek’s; extra Constructivist than New Goal, they’re constructed from coloured blocks organized so that every determine is directly typical and distinctive, objectified and customized. Behind them, flat planes of commercial iconography—not not like the Isotype designs by fellow Cologne artist Gerd Arntz displayed close by—set the scene.

Because the curator Lynette Roth has proven, Seiwert derided a lot New Objectivity as “bieder,” a pejorative evocation of the pre-1848 Biedermeier period. Just like the 1920s, this era had elevated the center class and, alongside it, life like work with easy surfaces. Seiwert believed in portray—he was fond, like many Cologne artists, of artwork from the late Center Ages—however argued that, if painters had been to realize revolutionary solidarity with the working class, they must talk via type in addition to content material. To complement his legible, pictographic type, he made the surfaces of his canvases tough and brushy so viewers may learn them as merchandise of Handwerk, bodily issues made by folks—an enlivening mannequin of actual, unalienated labor which may domesticate the sensation, in flip, of a collective working topic. The place Hartlaub, in his letter to Barr, pressured the “materials foundations” of the brand new portray’s subject material, Seiwert stresses the materiality of the portray itself.

Postwar skeptics of New Objectivity prolonged the sooner critique that it affirmed its interval’s capitalist imperatives. For critics like Buchloh, the brand new representational portray was not merely misleading and elitist however given to pernicious nostalgia. Its artists glorified particular, and important, durations from the previous—antiquity, the Renaissance, and the mid-nineteenth century—which figured within the historic and ideological developments of capitalism and fascism. Certainly, official Nazi artwork, consolidated in 1937, privileged a chimeric figuration appropriated from these eras: a quasi-Classical, quasi-Romantic kitsch with idealized our bodies and distant, out-of-time settings. Some New Objectivity artists, like Grosz, transgressed these formal tips and appeared within the “Degenerate Artwork” exhibition that 12 months (or, as a result of they had been Jewish, queer, disabled, or leftists, suffered extra excessive persecution). However others, like Schad, participated within the concurrent “Nice German Artwork” present and maintained their careers into the 1940s.

Lampe and Ebner downplay this side of New Objectivity’s legacy, distancing it from the Nazis by embedding its artists in German modernism of the 1920s, a milieu that students typically oppose to Nazi artwork—in addition to to different “returns” of illustration, like Soviet socialist realism—on aesthetic and ideological grounds. Nonetheless, the curators do admit some continuity between the 2 durations in an “epilogue” to the exhibition and catalog. Right here, one sees that Sander photographed each uniformed Nazis and political prisoners within the type of his prior output and learns concerning the 1933 “cultural Bolshevism” exhibition at Kunsthalle Mannheim, which eight years earlier had been the location of Neue Sachlichkeit. A meticulous portrait by Grosz of the disabled, left-wing author Max Herrmann-Neisse (1925) was in each of those reveals, displayed first in a constructive mild, later in a adverse one. Now on view within the Pompidou’s second room, it reminds guests that the Nazi artwork program, like its politics, was reactive and contradictory, rejecting New Objectivity’s social content material whereas synthesizing elements of its realist type.

If New Objectivity was “within the air” within the 1920s, then, a few of its aesthetic positions and social bases percolated into the Nazi interval, typically with out friction (the catalog contributor Olaf Peters has written convincingly on this dynamic). Some New Objectivity artists had already earned the nationalist tag “New German Romanticism” by 1931; and, as Bloch and Kracauer famous, swaths of the brand new center lessons who typified New Objectivity’s viewers additionally grew to become supporters of fascism to shore up their newfound standing in opposition to these of the working class and of migrants flocking to the cities from the countryside and outlying territories, displaced by business or imperialism. (Simply two work within the present depict folks of shade and just one, Lotte B. Prechner’s Epoche [1928], with centrality or sensitivity; the opposite, by Dix, is a racist caricature.)

Whereas New Objectivity’s artists sought social which means for his or her work by relating it to different technique of manufacturing akin to workplace and home labor, the Nazis turned this sensibility right into a valorization of “inventive work.” Staff, of their view, would defeat alienation not via class battle however via a uniform dedication to the ethnic nation. The hoped-for collective topic of the Weimar interval had dispersed; as within the manufacturing unit, every employee, instrumentalized, turns into an object. By the mid-1930s, New Objectivity as a time period and as a cohort of artists had dispersed, too. However the historic contradictions that structured it held, and maintain, quick. The ultimate line of the tune’s refrain was prescient: “It’s within the air,” it went, “and never going anyplace!”

[ad_2]

Source link